I remember, as a child, having a recurring dream that I woke up one morning and the world had changed completely. All the people were gone. My family, my playmates, all the neighbors, and all the hustle and bustle of cars and people in my neighborhood in San Francisco had vanished. I wandered around looking for people, but found not a one. Always in the dream my destination was the neighborhood food store—called C Market—where we purchased all our food. I would walk into the store and think “Well, at least I will have food to eat until someone comes along to take care of me”.

Now I live at the EcoVillage campus of The University of Ascension Science & the Physics of Rebellion with people from around the world who have been guided by celestial beings to grow food because:

- The best way to obtain nutritious food that complements and supports spiritual ascension is to grow it ourselves.

- The probability of the demise of civilization as we know it increases with every decision and action “society” makes to destroy the web of life on the planet.

The University of Ascension Science & the Physics of Rebellion is all about sharing what we have learned with others. Our outreach to the world is extensive and our inreach to friends and neighbors here in the borderlands is broad.

I am acutely and painfully aware that while I enjoy freshly harvested, seasonally tuned, deliciously prepared food every day, there are thousands of people within a relatively short distance of my home that are hungry and some who do not know when they will next eat. There are thousands more who have access only to food that lacks essential nutrition. And all of us are in real jeopardy of having the experience of waking up one day to a very different world where the trucks no longer deliver food to the grocery stores, the power is off, and no water comes out of the tap.

I am acutely and painfully aware that while I enjoy freshly harvested, seasonally tuned, deliciously prepared food every day, there are thousands of people within a relatively short distance of my home that are hungry and some who do not know when they will next eat. There are thousands more who have access only to food that lacks essential nutrition. And all of us are in real jeopardy of having the experience of waking up one day to a very different world where the trucks no longer deliver food to the grocery stores, the power is off, and no water comes out of the tap.

There are many ways for us human beings to adapt our collective lifestyles towards working together to insure that everyone is cared for. This borderland region (in southern Arizona) is rich with histories of people who lived in close harmony with the land that provided well for them in eras of the past. As we move forward into the future, what can we learn from history about how to live sustainably in this bioregion? It is my hope that many people from around the world will join (wherever they are guided to live) in practicing what we at our EcoVillage campus call “divine administration principles”. Doing so will naturally weed out the unsustainable practices that arise from the culture of greed and in turn build environmentally harmonic, resilient, and dynamic practices that arise from the culture of caring.

Diaspora: The Scattering Of People From Their Original Country To Other Places:

Mass Dispersion Of An Involuntary Nature

The diaspora/migrations of people from many other countries through this borderland region is a travesty that involves lack of security of every kind (including food) for these travelers. How many people will be departing California and heading east as the water in their region goes dry and the radiation from Fukishima permeates the western shores of America? How many will head west fleeing the storms on the East Coast and the tornadoes in the Heartlands? What migrations from the North will be triggered by all the environmental changes of global warming? The world is changing fast and the “every man for himself” mentality is not the answer.

I once attended a workshop called “Refugees 101” given by Iskashitaa in Tucson. Iskashitaa’s harvesters are an inter-generational group of refugees from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East who partner with local Tucsonan volunteers to harvest approximately 100,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables each year from backyards and local farms. These nutritious foods are then distributed to refugee families from many countries and other Tucson organizations that assist food insecure families.

We did an exercise during this workshop that woke me up to the horrific experience of having to flee your home (because it’s not safe to be there) with no idea of where you will end up.

They put us into groups and gave us a scenario where an army from California invades Tucson and takes over the territory. As the scenario unfolded we were asked questions like: In what direction do you head? What do you take with you? What do you do when your car runs out of fuel? Do you have anything with you to bribe soldiers with that you meet along the way? What do you do if a family member becomes sick or injured along the way? If you head south, and make it to the border, and find it is closed, how will you get across? If you manage to cross the border and get caught and sent back to Arizona, and you are separated from your family members, what will you do?

This exercise brought home the hard reality of being a refugee. When you imagine this scenario in the geographical location that you are familiar with, it becomes much more real.

The Kino Border Initiative

The people in the borderlands are blessed to have many organizations that are making heroic humanitarian efforts to care for stranded travelers. One of these organizations is the Kino Border Initiative (KBI).

The people in the borderlands are blessed to have many organizations that are making heroic humanitarian efforts to care for stranded travelers. One of these organizations is the Kino Border Initiative (KBI).

The Kino Border Initiative is a bi-national organization that works in the area of migration and is located in Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. The KBI was inaugurated in January of 2009 by six organizations from the United States and Mexico: The California Province of the Society of Jesus, Jesuit Refugee Service/USA, the Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist, the Mexican Province of the Society of Jesus, the Diocese of Tucson, and the Archdiocese of Hermosillo. High School students from the Lourdes Catholic School in Nogales, Arizona are also an integral part of the KBI.

Every year, thousands of migrant men, women and children are deported to Nogales, Sonora, Mexico after trying unsuccessfully to enter the United States. They often arrive with only the clothes on their backs and a small plastic bag that contains their belongings. They often do not know where to turn to receive a meal, find shelter, and to make a phone call. They also arrive emotionally and psychologically devastated, due to separation from their family members or the inability to work legally in the United States. Many of those from Latin America and other countries are fleeing from poverty, drug cartels, and extremely dangerous and violent situations in their homelands.

Every year, thousands of migrant men, women and children are deported to Nogales, Sonora, Mexico after trying unsuccessfully to enter the United States. They often arrive with only the clothes on their backs and a small plastic bag that contains their belongings. They often do not know where to turn to receive a meal, find shelter, and to make a phone call. They also arrive emotionally and psychologically devastated, due to separation from their family members or the inability to work legally in the United States. Many of those from Latin America and other countries are fleeing from poverty, drug cartels, and extremely dangerous and violent situations in their homelands.

The Kino Border Initiative staffs three services/ministries that respond to the critical humanitarian needs of deported migrants:

- Aid Center for Deported Migrants (CAMDEP—Initials in Spanish) The CAMDEP provides two meals a day to migrant men, women, and children deported to Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. They serve over 45,000 meals per year. The CAMDEP also distributes clothing and personal care items, and refers people to Mexican government services. The KBI is blessed by the collaboration of organizations such as the Samaritans of Green Valley, No More Deaths, The Border Community Alliance and its partner organization FESAC in Mexico, as well as parishes and individuals from Phoenix, Tucson, and Ambos Nogales.

- Nazareth House is a shelter for migrant women and children, to respond to their vulnerability in the streets of Nogales, Sonora. It is a safe space where women and children can bathe, eat, sleep, call their families and reflect on their experience. They receive opportunities for prayer and pastoral support as well. Nazareth House gives sanctuary to over 500 people each year.

- First Aid Station. Many deported migrants arrive in Nogales, Sonora with severely blistered feet, flu symptoms, and dehydration. First-aid assistance is offered at the CAMDEP.

The KBI has an informative website that includes touching photos of the Aid Center in Nogales, Sonora and a short, very revealing documentary about their work.

While ministering to the people, the KBI regularly conducts a survey to obtain basic information about the people served and to document abuses committed against them. An article is available online that describes valiant efforts to help thousands of families stuck at the border and struggling to find a safe place to live. To view go to: https://kinoborderinitiative.org/close-to-home-how-migrant-integration-fosters-a-cycle-of-dignity/

If you are interested in helping the KBI to “humanize the border” contact Ivette Fuentes: ifuentes@kinoborderinitiative.org

Community Food Bank Of Southern Arizona

One in five Arizonan’s lack the basic necessity of having sufficient food to eat. This is worse than the national average where one in seven people are experiencing food insecurity. One in four children in Arizona is struggling to eat. That is more than 450,000 statewide. 58,000 of them live in Pima County. School administrators report that it is difficult to make sure that students are eating once they leave school for the day or for the holidays. A lot is left on the shoulders of the children and in many cases they are fending for themselves. They don’t know where the food banks are and they don’t want to go alone. 27% of Arizona households make too much money to qualify for nutritional assistance, but they aren’t making enough to provide daily meals. Apache, Yuma, and Navajo counties have the highest overall rate of food insecurity in the state.

A survey commissioned by the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC) found that one in four Americans worries about having enough money to put food on the table in the next year. Food insecurity is associated with chronic health problems in adults including diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and mental health issues including major depression.

The Amado Food Bank (which is a branch of the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona) is serving nutritious breakfast and midday meals on school playgrounds, in parks, camps, and other sites where children traditionally congregate in the summer months.

The Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona provides food and food-related services throughout a 23,000 square-mile region of Southern Arizona including Pima, Cochise, Graham, Greenlee, and Santa Cruz Counties. The Community Food Bank distributes over 63,000 meals a day to members of our community with the support of over 300 local nonprofit agencies. Each year they assist over 225,000 people with their services. They provide distribution services from their main warehouse in Tucson and from four branch banks in Nogales, Green Valley, Amado, and Marana.

The Community Food Bank serves the food insecurity needs of many southern Arizonans, but they do so much more. Their programs range from education and advocacy to helping families set up household and community gardens, and coordinating farmers’ markets. If you would like to assist the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona to meet the food needs of the hungry in our community please contact them through their website at www.communityfoodbank.com.

Food Corps

Food Corps is a nationwide team of AmeriCorps leaders who connect kids to real food and help them grow up healthy. Food Corps members partner with schools to put in place a three-ingredient recipe for healthy kids, creating a nourishing environment for all students. They provide:

- Knowledge: food and nutritious education that gives kids the information they need to make smart choices

- Engagement: hands-on activities like gardening and cooking that foster skills and pride around healthy food

- Access: lunch trays filled with nutritious meals from local farms

Thousands of young Americans have dedicated themselves to reforming the food chain, from field to table, and with programs that have emerged to channel that energy and idealism. Food Corps is dedicated to creating a future in which all our nation’s children—regardless of class, race, or geography—know what healthy food is, care where it comes from, and eat it every day.

Food Corps sees unique opportunities in Arizona for reaching their goals. Arizona is diverse in both landscape and culture. While many parts of Arizona experience winter snowfall, much of the state stays warm enough to grow crops year-round. Arizona’s warm desert climate is known for citrus, cotton, and lettuce production. Yuma and its surrounding area provide 90% of leafy vegetables grown in the United States during the winter months. Because perennial streams and rivers are rare, farmers and gardeners strive to find sustainable means for food production, including water-harvesting and indigenous seed selection.

Arizona is diverse in culture as well. The state is home to 22 Indian tribes. The history and culture of each tribe shapes the local landscape in distinct ways. Because Arizona was historically part of Mexico, Southern Arizona is still fundamentally integrated with Mexican culture. Food Corps service members currently serve in five Native American communities within the state, which gives them the space to learn about Native, Mexican, and Southwestern food cultures while developing a deeper understanding of how to grow food in this unusual climate.

Back To Our Agricultural Roots

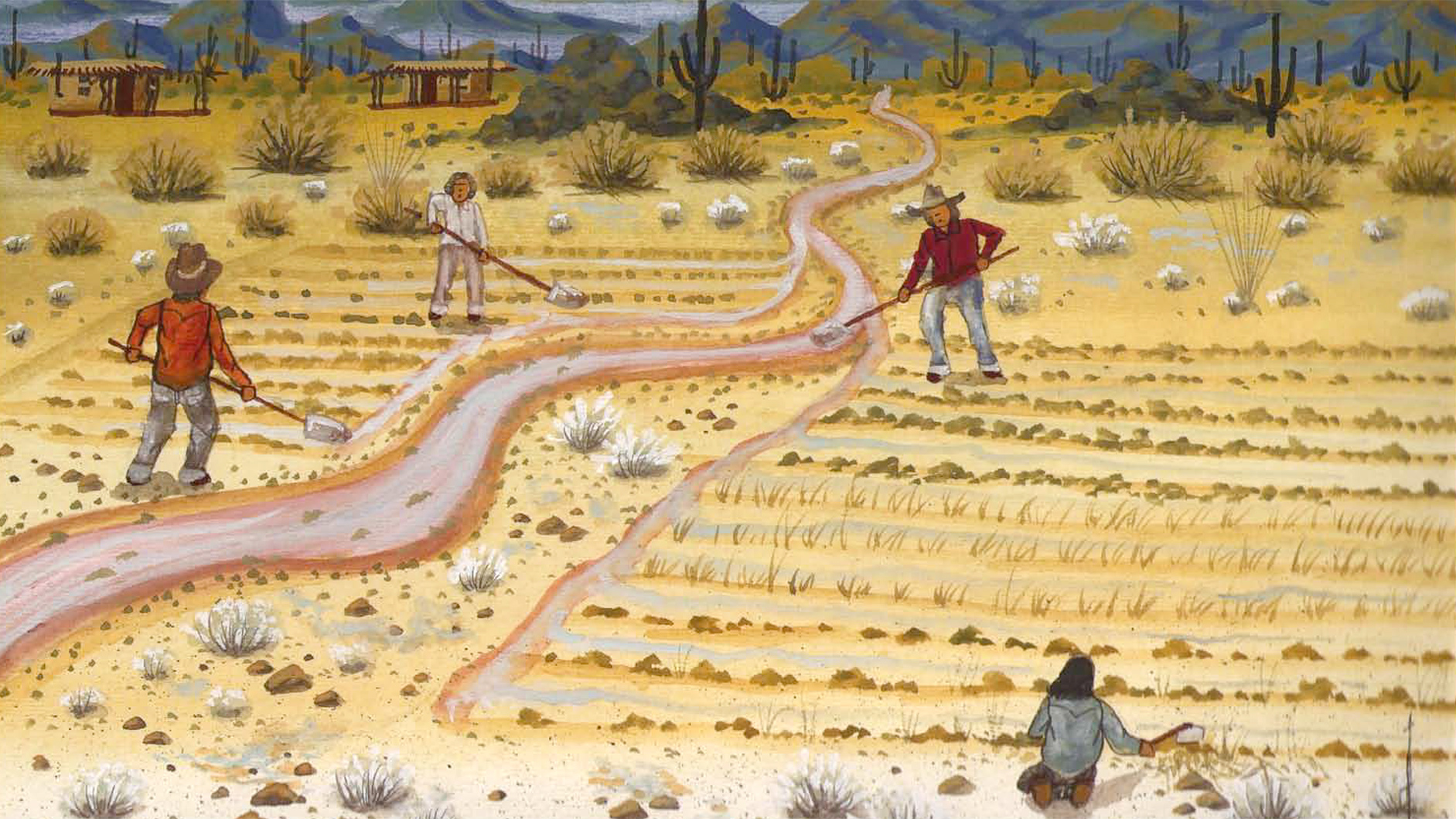

In this borderland region there have been many historical eras where people worked successfully together, in ways that harmonized with the carrying capacity of the place, to create food security for their communities. Because this is an arid region, farming here has always necessitated techniques that are now becoming essential to people who are growing food in the rapidly increasing arid regions of the planet. Techniques such as rainwater harvesting and storage, farming along drainages which are given encouragement to attract and retain rainwater, using drought resistant plants, and growing crops attuned to the place they are planted are necessary tools for farming in arid regions where ground water depletion is no longer an option.

I attended a fascinating presentation on “Traditional Approaches to Modifying the Environment for Productivity and Sustainability along the Santa Cruz River” by Suzy K. Fish and Paul R. Fish at the Fifth Annual Santa Cruz River Research Days in 2013. They presented many methods of water retention for farming that were used in days gone by and many of which are still being used by farmers in Sonora, Mexico. You can view this presentation on the Sonoran Institute website in the section on the Santa Cruz River Researcher Days by clicking on the presentations for 2013. Another fantastic local resource for joining the movement in Southern Arizona to design and build systems that catch the precious rains and channel the water to nurture our lives is the Watershed Management Group in Tucson. You can find out more about them at: https://watershedmg.org.

I attended a fascinating presentation on “Traditional Approaches to Modifying the Environment for Productivity and Sustainability along the Santa Cruz River” by Suzy K. Fish and Paul R. Fish at the Fifth Annual Santa Cruz River Research Days in 2013. They presented many methods of water retention for farming that were used in days gone by and many of which are still being used by farmers in Sonora, Mexico. You can view this presentation on the Sonoran Institute website in the section on the Santa Cruz River Researcher Days by clicking on the presentations for 2013. Another fantastic local resource for joining the movement in Southern Arizona to design and build systems that catch the precious rains and channel the water to nurture our lives is the Watershed Management Group in Tucson. You can find out more about them at: https://watershedmg.org.

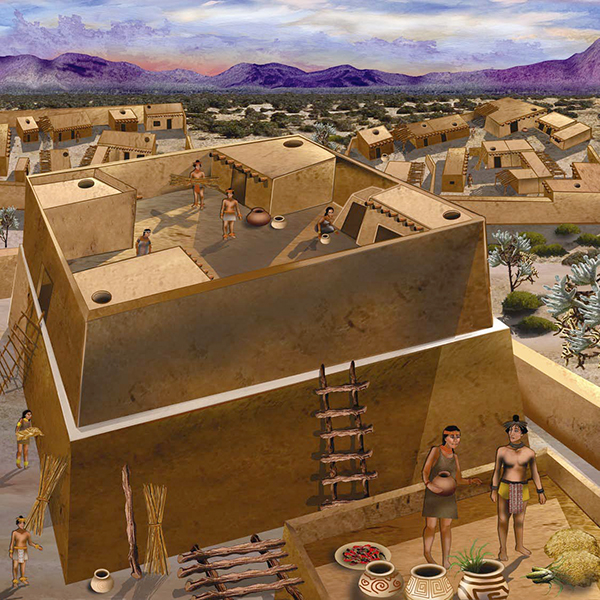

Centuries before Europeans first saw the Tucson basin, a group of Indians with a distinctive way of life had settled here. Known today as the Hohokam, these people built villages close to streams in order to farm the region’s rich bottomlands. They lived in this region from about A.D. 300 to 1500. They ably adapted themselves to the desert environment by farming along drainages and hunting and gathering in the desert and mountains.

The Hohokam people were not the first to live in the Tucson basin. The use of grinding slabs marks the beginning of the Desert Archaic tradition which lasted from 7000 B.C. to about A.D. 300. The very first evidence of maize cultivation in the Southwest dates from about 2100 B.C. Evidence of flood canals that supported farms growing bottle gourds, cotton, common beans, tepary beans, grain amaranth, squash, tobacco, and maize in the Tucson and Santa Cruz Basins date their origins at about A.D. 750.

Father Eusebio Francis Kino, an Italian-born Jesuit missionary, was the first European to explore and map the area. He established many missions in the region and introduced Old World crops such as barley and peaches. Father Kino is also responsible for bringing wheat (formerly introduced to Northern Mexico by earlier missionaries) up into this region.

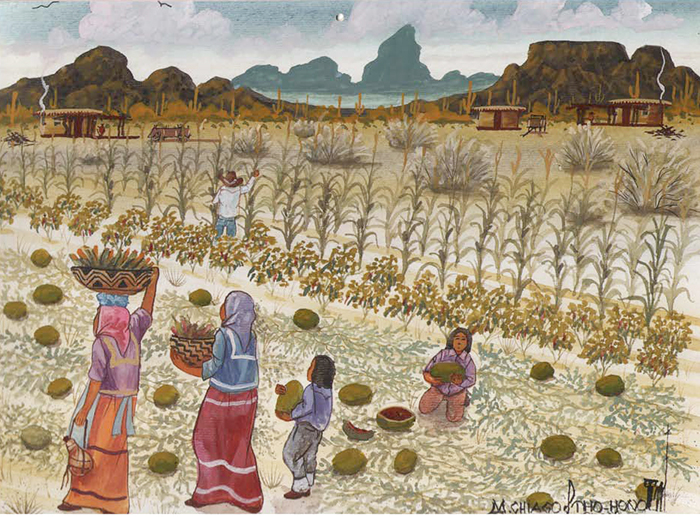

TOCA and Native Seeds/SEARCH

Tohono O’Odham Community Action (TOCA) and Native Seeds/SEARCH (NS/S) are two organizations that are promoting wild food sources and desert-tolerant crops. The knowledge of dry-land farming and wild-plant harvesting of foods in this region—as well as seed varieties adapted to dry weather—are like flickering embers on the landscape. TOCA and Native Seeds/SEARCH are seeking these precious treasures out and nurturing them into flames, so these essential parts of the past can be brought forward into the future.

TOCA was started in 1992 by Terrol Dew Johnson with the vision to promote a culturally rich lifestyle for Tohono O’Odham. Because of the widespread introduction of processed food, and the almost total disappearance of using traditional food sources, the Tohono O’Odham are twice as likely to be diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. The real victims are the young Native Americans, specifically those between the ages of 10 and 19, who are nine times more likely to be diagnosed with the disease. From 1990 to 2009, diabetes diagnoses rose 110% for the age group.

Initially, TOCA was an after-school program for students on the reservation. The community elders would take children out to the desert where they would learn to harvest wild plants such as saguaro cactus and cholla buds.

TOCA is now a multi-faceted organization that includes Native Foodways Magazine, and various community initiatives that are fostering self-sufficiency for the Tohono O’Odham people.

Native Seeds/SEARCH is doing heroic work in its quest to revitalize crops that thrive in an arid climate. This Tucson-based seed conservation organization was started by Gary Nabhan and Mahina Drees in 1983 while working with the Tohono O’Odham to establish gardens for their sustainable food needs. They were inspired to become collectors and preservers of endangered traditional seeds after tribal elders told them that what they really needed was the seeds for the foods their grandparents used to grow.

Native Seeds/SEARCH has now grown from a humble operation with seeds stored in chest freezers to an organization recognized as a leader in the heirloom seed movement. Over 500 varieties of seeds are grown on their Conservation Farm in Patagonia, AZ and distributed to traditional communities and gardeners around the world. All together, NS/S has roughly 500 varieties of corn, nearly 200 types of beans, and 1,300 other types of seeds. These seeds are essential to preserving the agro-biodiversity of the arid Southwest.

Sonoran Soft Winter Wheat

The borderland region is experiencing the resurrection of Sonoran White Winter Wheat, which is also known as Trigo Flour, Sonora Blanca (Spanish), and ‘olas pilcan (O’Odham). This drought and disease resistant wheat that thrives in the arid Sonoran landscape was originally brought by Spanish and Italian missionaries to the Opata and Lowland Pima Indian farmers near Tuape, Sonora, Mexico in the seventeenth century. When Father Kino arrived in Sonora in 1687, he brought the now well-established crop northward.

White Sonoran Wheat is one of the oldest surviving wheat varieties growing anywhere in North America. Predating the Red Fife and Turkish Red Wheat, it is a soft, round-grained winter wheat with pale red grains that grow on beardless heads. It takes 90 days to reach maturity when planted in the spring and also performs well when planted in the winter. It was widely planted in California by the early 1800s and provided most of the West Coast residents (as well as nearly all troops) with their flour during the Civil War. By the 19th century commercial production of this sweet and tasty wheat was in decline. It was produced minimally up into the 1970s but since then has not been used in commercial production anywhere on the continent. Norman Borlaug, a Nobel Prize-winning plant breeder, used White Sonoran Wheat as drought-adapted breeding material for the Sonora 64 variety which was one of the first Green Revolution’s wheats. Unfortunately, development of Sonora 64 led to the complete commercial demise of White Sonora Wheat by 1980.

White Sonoran Wheat is one of the oldest surviving wheat varieties growing anywhere in North America. Predating the Red Fife and Turkish Red Wheat, it is a soft, round-grained winter wheat with pale red grains that grow on beardless heads. It takes 90 days to reach maturity when planted in the spring and also performs well when planted in the winter. It was widely planted in California by the early 1800s and provided most of the West Coast residents (as well as nearly all troops) with their flour during the Civil War. By the 19th century commercial production of this sweet and tasty wheat was in decline. It was produced minimally up into the 1970s but since then has not been used in commercial production anywhere on the continent. Norman Borlaug, a Nobel Prize-winning plant breeder, used White Sonoran Wheat as drought-adapted breeding material for the Sonora 64 variety which was one of the first Green Revolution’s wheats. Unfortunately, development of Sonora 64 led to the complete commercial demise of White Sonora Wheat by 1980.

The mills of Sonora that grinded this heritage grain are now crumbling all over Sonora, Mexico. Luckily, Gary Nabhan of Native Seeds/SEARCH found some viable seed tucked away in Mexico and has inspired several farms in Southern Arizona to start growing the White Sonoran Wheat again. The Avalon Gardens & EcoVillage agricultural department has participated in the resurgence of growing this wheat, which is so appropriate for our bioregion.

Separating The Wheat From The Chaff

Is it obvious to you that the people of the world are separating into two diverging streams? On the one hand we have the old order of colonizing greed and on the other the new order of compassionate seeds. The people who have created a world where profit and power is based on a system that tears apart families and destroys ecosystems are very different from the people who volunteer to feed and clothe and put bandages on the feet of brothers and sisters who have gone through hell to come to America in hopes of a better life (like many of our ancestors did unless we are of Native American lineage).

Is it obvious to you that the people of the world are separating into two diverging streams? On the one hand we have the old order of colonizing greed and on the other the new order of compassionate seeds. The people who have created a world where profit and power is based on a system that tears apart families and destroys ecosystems are very different from the people who volunteer to feed and clothe and put bandages on the feet of brothers and sisters who have gone through hell to come to America in hopes of a better life (like many of our ancestors did unless we are of Native American lineage).

And yet, no matter how “green” we are, we still have to compromise and actually support and subsidize the corporate empire of greed.

Let’s create a boycott of the 1% by designing a social networking formula so that people, who realize the enormity of our present global situation and are willing to do what it takes to starve the beast and feed the flowering future, will have the information they need to direct their money and their energy into deserving companies and organizations.

History has proven that boycotts work. They are the only strategy that has caused evil governments or businesses to fail. Is it not time to support those pioneers of promise that are building a new way of life—both globally and locally?

The Vine and Fig Tree

(traditional Israeli song)

And everyone beneath their vine and fig tree

Shall live in peace and unafraid.

And everyone beneath their vine and fig tree

Shall live in peace and unafraid.

And into plowshares turn their swords,

Nations shall learn war no more.

And into plowshares turn their swords,

Nations shall learn war no more.